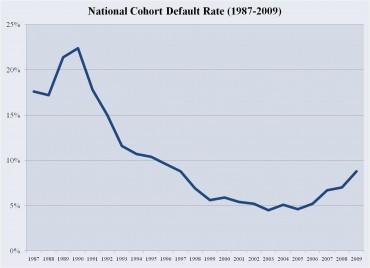

Student loan default rates on are on the rise, according to data released by the U.S. Department of Education earlier this week. The student loan default rate nationally climbed to 8.8 percent for fiscal year 2009, the highest the national default rate has been since 1997.

It shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise: Student debt eclipsed both national credit card debt and the $1 trillion mark in 2011, during the worst sustained economy for young adults in decades.

“Borrowers are struggling in the economy. We see a strong relationship between student-loan default and unemployment rates,” said U.S. Deputy Undersecretary of Education James Kvaal in a press call Monday.

With changes to the higher ed financing system in the past few months, though, student debt may actually grow.

The summer’s debt ceiling and deficit reduction debate cut over a trillion dollars in government spending. One target was federal financing of higher education, which was slashed by nearly $22 billion over the next ten years.

The cuts included the elimination of subsidized graduate student loans and a special credit for students who make their loan payments on time for at least 12 months. Of the $22 billion saved, about $17 billion will be directed toward preserving funding for Pell Grants, one of the main federal aid programs for undergraduate students.

Graduate students, on the other hand, will bear much of the brunt of the recent series of cuts. According to Richard Vedder, the director of the Center for College Affordability and Productivity, graduate student aid represents a more appealing political target.

“It is less politically popular to say that we will also provide support through the master’s or PhD or professional school level,” he said.

Karen Cooper, director of the Stanford Financial Aid Office, said that the recent federal cuts would force graduate students to seek alternative sources of funding and could increase levels of debt at the margin.

Prior to the recent legislation, graduate students were able to borrow up to $8,500 through a subsidized direct loan program. Next year, that option will no longer exist, so interest will accrue during in-school and grace periods. In short, as Cooper said, “The loan will be more expensive.”

Furthermore, Cooper indicated that a second federal aid program–the Perkins Loan Program–may be on the chopping block, as well. The Perkins program provides schools with a large amount of money to create a revolving fund used for subsidized loans. According to Cooper, the government has not provided additional funding since 2000, but could choose to take the money back. The overall pot at Stanford–a mixture of federal and Stanford money–represents nearly $80 million and is used in $6,000 increments per student per year.

While graduates have been hit hardest thus far, many higher education experts have said that undergraduate aid could be next. According to Mamie Lynch, a policy analyst at the Education Trust, undergraduate aid programs may face future cuts as well.

“Pell Grants will be preserved for the first year, but in the year after, there could be more cuts,” she said. “And Pell would be in danger under those cuts.”

Pell Grants are limited to undergraduate students with demonstrated need, and are not loans. The maximum Pell Grant amount for the 2010-11 school year was $5,500.

A number of factors make federal higher education aid an increasingly likely target for spending reductions. According to Vedder, the political risk associated with cutting federally-backed student loans is significantly smaller than the risk of scaling back the political lightning rods of Medicare and Social Security. Even many Democrats, Vedder said, have become increasingly open to the idea of placing performance standards or additional timing restrictions on Pell Grants.

At the national level, student debt, driven by rising costs of higher education, has skyrocketed.

Malcolm Harris, an education contributor for n+1 magazine, said student debt now totals nearly $1 trillion and has surpassed credit cards as the nation’s single largest source of debt.

Costs have significantly outpaced inflation, growing at an average rate of 6 to 7 percent per year over the past few decades. According to Vedder, growth rates at that level “signify a doubling of costs every decade and a quadrupling over two decades.”

And according to many commentators, the growth rate shows no signs of abating.

“You don’t have to be Miss Cleo to see increases in the near-future,” Harris said. “The (University of California system) is seeing another year of huge increases, for example. At the rates of tuition inflation, huge increases have been the standard for a couple decades now.”

Due to a combined $900 million budget cut to the UC and California State University systems, the schools saw 10 and 12 percent tuition increases this year. Pennsylvania’s system is even worse: In-state students at flagship Penn State now pay more than $15,000 in tuition.

Growing levels of debt as a result of cost increases have made federal financial aid programs more impactful but have also placed such aid programs at risk.

“The student debt crisis has increased the willingness to consider restrictions or modifications on student loan programs,” Vedder said. “The stage has been set for some long-term cutbacks in federal aid programs.”

Alex Katz is a staff writer for the Stanford Review. He is a contributor to The College Fix.

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.