Humanities programs devastated by critical theory could save their disciplines by going back to the basics

College English and humanities professors who came of age in the last few decades have abandoned their traditions and sold their students short.

These professors could have guided their charges in learning beautiful forms of expression, truths about human nature, and great ideas of wisdom, love, virtue, piety and the good life — among many other treasures.

Instead, they sidelined literature and high culture to focus on philosophical theories about topics trending in academia, such as race, representation, capitalism, sexuality and gender. Many of these these theories come from twentieth century far-left writers such as the French philosophers Derrida and Foucault and the Marxist Italian Antonio Gramsci — and their many lesser acolytes and imitators.

Yes, some classic works — or, perhaps more likely, contemporary ones chosen for their authors’ race, gender, or sexuality — still appear on syllabi, but professors are so steeped in critical theory that the works themselves are secondary. They are taught as little more than “texts” illustrating leftist political ideologies or narrow theories of representation and culture.

Even worse, professors have attempted to teach students this “theory” without the basic background training in philosophy or other disciplines required to understand it and evaluate it independently.

Some of these literature scholars have been reflecting lately on this state of affairs. A few have even suggested that the study of English and other humanities disciplines may have lost its way around the 1970s, when professors besotted with imported European philosophy started making their profession all about “theory,” which seemed much more exciting and politically relevant than the careful, respectful examination and close readings of epics, poems, novels, and plays.

Those professors went on to teach generations of students in the 90s and later. Michael Clune, a professor of English and the humanities at Case Western University who came up in that era, described the scene in a recent article for the highbrow Los Angeles Review of Books:

“When I was an undergraduate in the 1990s, the witchy logic and arcane vocabulary of high theory served as a key to the malevolent forces hidden by the oppressive, indomitable, literalist common sense of the government, the media, the corporate world,” he wrote.

That is convoluted, but Clune makes some good points:

The humanities disciplines, after the theory revolution of the 1970s and ’80s, no longer presented themselves primarily as centers of disciplinary expertise, which require long apprenticeship to practice effectively. Instead, they became boxes holding a special kind of thought. This thought required no expertise or long training to practice effectively. In theory, anyone could do it.

Now…this style of thought and vocabulary has been lifted from the box of the English department and placed in the infinitely better-furnished and more spacious boxes of some of society’s most powerful institutions.

When English professors rejected their own legacy, they opened the Pandora’s box of critical theory — and they unleashed woke ideologies on the campus and then the broader culture. Mark Bauerlein, a writer and English professor emeritus at Emory University, described the shift in an essay last year.

When American English departments tossed out the literary canon in the 1980s, they discarded cultural coherence and patriotism and replaced it with cynicism, identity politics, and cultural nihilism, Bauerlein argued in Chronicles: A Magazine of American Culture.

Today literature departments are a “wilderness of courses straying into identity politics, media, and various agenda-driven critical theories, with some novels and poems serving as pretexts,” Bauerlein wrote in his essay. “There’s no coherent sequence that students must master, no tradition but the rejection of tradition as elitist, racist, sexist, and all the rest.”

Bauerlein wrote that initially he and his colleagues believed the cultural chaos promoted by English professors would stay in college. He was wrong. As Andrew Sullivan wrote for New York magazine in 2018, two years before he resigned for having unacceptable opinions, “We all live on campus now.”

In the last decade, “blather about ‘capitalism and patriarchy and whiteness’” has moved from elite literary circles to the center of progressive politics, Bauerlein said. Not only has it permeated universities and elite media, it has invaded major institutions from the military to professional science to elementary schools.

Your average contemporary DEI administrator is likely well-versed in phrases like “critical race studies” and “marginalized identities,” concepts derived in part from postmodern philosophy and cultural Marxism, which seemed so hip and new to humanities professors and majors a few decades ago.

For Professor Clune, “the question [now] arises: what can an English professor teach someone about race, class, gender, or capitalism that they can’t learn on the internet or Netflix?”

To which I add, what can a contemporary English professor teach someone about race, class or gender that she won’t get in her required college and, later, corporate diversity trainings? Given the institutionalization of “theory,” why teach it in courses at all?

Literature professors should learn again to see beauty and wisdom, not just race and gender

Here’s how I advise English and other humanities professors to win new majors after losing so many, perform a valuable service, and resurrect their disciplines: teach how great artists innovated and refined their work. Some professors – mostly at religious schools – still do this, but apparently, most don’t anymore.

Here’s critic and exiled English professor William Deresiewicz on the subject at Quillette:

Anyone in the academic humanities…will see the problem. Loving books is not why people are supposed to become English professors, and it hasn’t been for a long time…

Novels, poems, stories, plays: these are “texts,” no different in kind from other texts. The purpose of studying them is not to appreciate or understand them; it is to “interrogate” them for their ideological investments (in patriarchy, in white supremacy, in Western imperialism and ethnocentrism), and then to unmask and debunk them, to drain them of their poisonous persuasive power. The passions that are meant to draw people to the profession of literary study…are not aesthetic; they are political.

Deresiewicz, who earned a doctorate at Columbia and taught at Yale, saw up close how elite English departments had abandoned aesthetics and careful study for politics and theory. Like so many others, he came to want nothing to do with it.

I do not have Clune or Deresiewicz’s advanced learning or experience, but I share their disillusionment.

As a young person, I had an aesthetic passion for literature the same way other girls adored pop albums or obsessed over cute boys.

My adult intellectual life began in Miss Rice’s Catholic school eighth-grade class reading “The Odyssey” with stars in my eyes, thrilling to its exquisite language, its subtly expressed longings for both home and adventure, and the knockout epic simile describing Odysseus and Penelope’s marital reunion. I learned that passage at age 13 and can still recite it from memory:

Now from his breast into the eyes the ache

of longing mounted, and he wept at last,

his dear wife, clear and faithful, in his arms,

longed for as the sunwarmed earth is longed for by a swimmer

spent in rough water where his ship went down

under Poseidon’s blows, gale winds and tons of sea.

Few men can keep alive through a big surf

to crawl, clotted with brine, on kindly beaches

in joy, in joy, knowing the abyss behind:

and so she too rejoiced, her gaze upon her husband,

her white arms round him pressed as though forever.

Reading poetry like that, I believed then that literature could show me the deepest things about being human.

But I lost my way when I went to college. My “comparative literature” professors with fancy credentials and dangerous charisma seduced me with bits and pieces of critical theory instead of nourishing the passion for literature planted so carefully by my middle and high school teachers and my wonderful parents.

I thought “theory” was très sophisticated and intellectual when I was 19, but now I wish I had never heard of it. I am convinced that my professors sold their birthright for a mess of pretentious and harmful ideas.

My fellow students and I deserved better. (As did our paying parents.) The undergraduate years are precious and often exorbitantly expensive. We should have been taught valuable skills and lessons that could sustain us through the inevitable confusions, battles, and sorrows of life.

The solution I demand is for professors to humble themselves and go back to the basics. Instead of deconstructing “texts” or using them as props for the latest edgy theory of oppression, college teachers should return to the careful, thrilling study of the intricacies of great works. They should approach them with attitude of respect towards what they have to teach us.

That return might go a long way to reforming university culture.

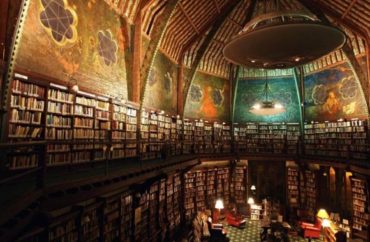

The wisdom and wonder is there; it’s all still in the library (unless the books have been replaced by nap pods).

Teachers and students need only to recover it again.

MORE: Woke scholarship killed the humanities. Love of beauty can save them.

IMAGE: Oxford University Libraries/The Oxford Union Library

Like The College Fix on Facebook / Follow us on Twitter

Please join the conversation about our stories on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, MeWe, Rumble, Gab, Minds and Gettr.